I was at the gym when my doctor called to say there was something very wrong with me and I needed to drive to the emergency room—immediately.

Looking back now on that day in December 2013, I should’ve been terrified. But I’d just graduated from the University of Minnesota and landed a job in Johnson & Johnson’s Sales Leadership Development Program as a sales analyst in Minneapolis. I was 21 and felt invincible—as if the doctor must have made some huge mistake. I actually asked him if I could finish my workout first. The answer was no.

It wasn’t that my health was perfect. That fall, I’d been bedridden for a week with extreme exhaustion. When I saw a doctor at the university, a blood test turned up mono. He also told me my platelets and blood cell counts were very low. In fact, he told me that if I slipped on a patch of ice, my blood wouldn’t clot and I could bleed to death.

I was concerned, of course, but I was also in the middle of finishing finals and trying to get home for the holidays. I chalked the mono and low platelet count up to being super-stressed, and made an appointment to see my family physician when I got to my mom’s house. He was the doctor who phoned me at the gym a few days later.

A shocking diagnosis

Once I got to the ER, I was admitted to the hospital and stayed overnight to be monitored. I met with an oncologist who suggested a short wait-and-see approach: I’d be released from the hospital, but for the next two weeks, I had to get my blood tested regularly. If, after two weeks, my platelets and blood cell counts were still low, they would need to do a bone marrow biopsy to get a clearer picture of what was going on. I ended up needing the biopsy. My body still trembles when I remember the procedure. They literally drilled into my backbone to pull out the marrow, and although they numbed the area where the needle went in, I was awake for the whole thing. The pain was excruciating—as was the week-long wait for the results.

The verdict: I had severe aplastic anemia (AA), a disorder where your bone marrow essentially stops producing blood cells for your body.

While my recovery felt slow, I was acutely aware that my outcome could’ve been so much worse. My best friend in the hospital was 18, and he was going through a transplant for leukemia. Two months after my successful transplant, he passed away.

At first, I thought, Fine! I’ll just take a few pills and monitor my blood levels. But when I searched for “AA” online, I quickly learned my condition—and treatment—would be much more involved.

When your bone marrow stops working, you need blood transfusions to stay alive. But you can only have so many before proteins can build up in your organs and become life-threatening. Many AA patients try another therapy, called anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG), which involves being injected with animal protein to try and restart the immune system and get the bone marrow working like it should.

I also found a YouTube video of a world-renowned AA doctor, Neal Young, M.D., talking about how bone marrow transplants were the most effective treatment, particularly for young people with the disease. I ran into my mom’s room to show it to her. I think it was in that moment that we both realized the gravity of my diagnosis.

After six months of weekly blood transfusions and even trying ATG therapy—which did help my blood counts slightly, although it wasn’t a sustainable fix—it was clear I needed a transplant. So my mom and I drove to the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., to see Dr. Young. As I’d suspected based on my Internet research, he recommended a bone marrow transplant—and a doctor in Milwaukee who could do the procedure, about an hour and a half away from my mom’s house.

Unfortunately, neither of my older brothers were a match. But I did find one through the National Marrow Donor Program Registry (now called Be The Match), and plans for my transplant were set in motion.

First, I spent eight days getting three different types of chemotherapy to incapacitate my immune system so it wouldn’t reject my new bone marrow. Then, in November 2014, I had the transplant, which replaced my unhealthy blood-forming stem cells with the healthy ones from my donor.

The first 100 days after a transplant are crucial—the fear is that your body will reject your new bone marrow. While my recovery felt slow—I was constantly exhausted and in pain, and my newly-developing immune system meant I was susceptible to any kind of illness—I was so fortunate in how smoothly it all went.

I was acutely aware that my outcome could’ve been so much worse. My best friend in the hospital was 18, and he was going through a transplant for leukemia. Two months after my successful transplant, he passed away.

My chance to live

Now, my day-to-day looks like that of any other 24-year-old. I do have occasional doctor’s appointments, and considering my new immune system, I get sick more often than most people.

But the biggest change this disease prompted has been my mindset: Facing my own mortality inspired me to realize that our greatest asset as humans is our vulnerability. Soon after I was diagnosed, I realized that no matter how many achievements I’d accomplished and goals I’d reached, I wasn’t going to be able to face this alone. My experience forced me to learn to depend on others—to fully embrace that it’s OK to not be OK—and that there’s power in sharing my story.Every day, I’m grateful for my chance to live. I’m grateful to my managers at Johnson & Johnson, who told me right after I was diagnosed that my job would be waiting for me when I got better—that they wanted me to focus on my health. I’m grateful to my family, friends and strangers for all of their support, my amazing doctors and especially my bone marrow donor, whom I got to meet last year.

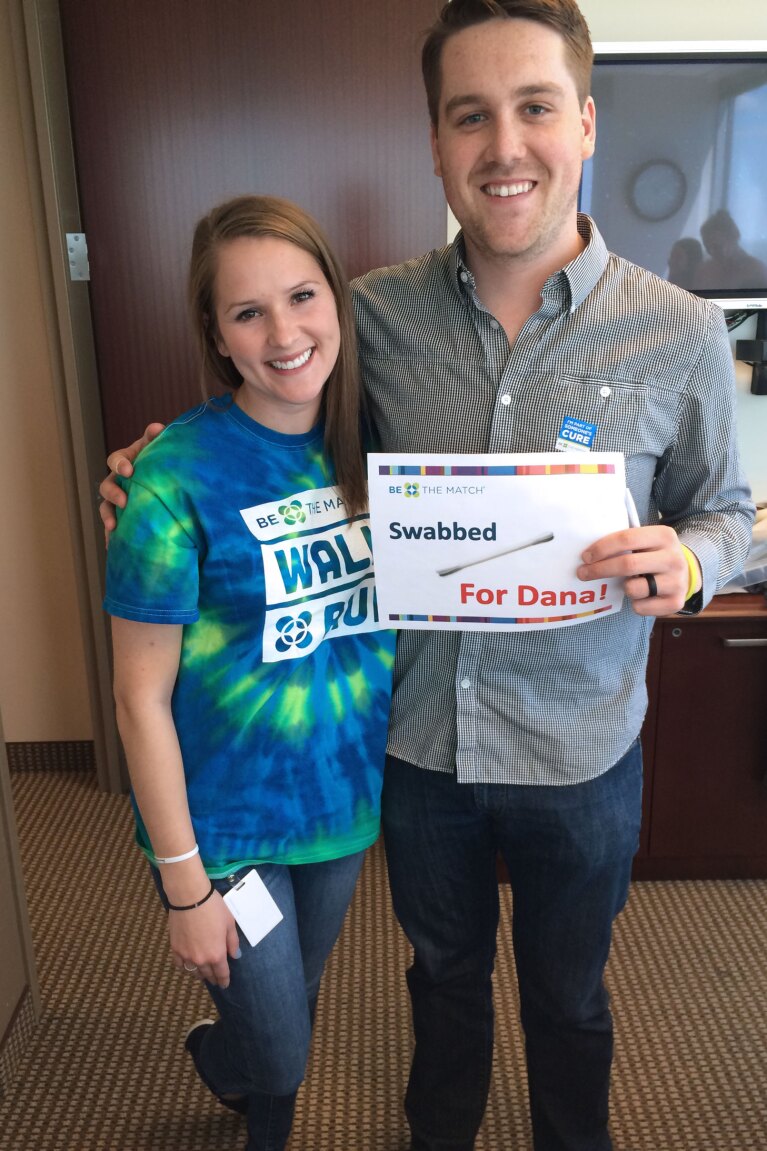

To do what I can to give back, I now run bone marrow donor drives, and I’m starting a Be The Match campaign at Johnson & Johnson to educate my co-workers about being a donor—and how it can save a life like mine.

You can help, too. Throughout March and April, Johnson & Johnson is partnering with DoSomething.org to help sponsor their Give a Spit About Cancer campaign: Go to the site and you can sign up to receive a cheek-swabbing kit that you can then send back to become part of the national registry. You can also learn about how to start a bone marrow drive at your college campus.

I always tell people that you may not think you have the time or resources to change the world, but you do have the opportunity to change one person’s world. I’m proof of that. And so is my donor, who signed up for the registry at his college.

Whether you decide to donate bone marrow or blood, or simply send a nice note to someone, always remember how impactful a single act of kindness can be.